Opening a restaurant is anything but simple. Whether it’s your first NRO (new restaurant opening) or your fifth, there are so many different elements to consider that it can make your head spin. While there are multiple “how to open a restaurant” guides you can review to get started (check out this great one from Toast, for example), these extensive checklists can easily feel completely overwhelming.

Since you can’t do 50 things at once, what should you prioritize when you want to open a restaurant? Where should you start? What do you really need for your NRO, and what’s a nice-to-have?

We decided to ask these questions to Jefferson Macklin, Partner at Traveler Street Hospitality, which has opened Bar Mezzana, Shore Leave, No Relation, and Black Lamb, all in the Boston area. Over his career, Jefferson has opened a total of seven different restaurants, and has deep knowledge of what works and doesn’t work when launching a new brand. Practical and balanced, he relishes working with the creative tension at the heart of all restaurant businesses: how do you balance creativity with profitable operations? As Jefferson says, “There are certainly easier avenues to take to make money, but I think launching a great new creative concept is a fight worth fighting for.”

Keep reading to learn what other words of advice Jefferson has for opening a new restaurant, including the similarities between music and restaurants, the importance of a killer menu concept, and why the allegory of the monkey and the pedestal may not apply when you open a restaurant.

Q: You have a background in managing musicians. How did you get started in the restaurant industry?

I actually started out in a completely different world. I grew up in a military family so I went to military school. When I graduated, I decided to go to business school because I was really interested in learning more about leadership and found my way into consulting.

I’ve always loved music—not as a performer, but as a fan. I figured if I could be in some way in the music industry, then that would be cool. I had student loans to pay, so I couldn’t really jump into music full time after graduating, but I always dabbled and would manage bands on the side. When I had an opportunity to join a startup that was music focused, I dove in. I helped launch Rock.com (a music site at the time). In the process, I learned a lot about what it takes to run an organization, and what it takes to capitalize an organization.

What I really loved was the creative tension—trying to make a living while you’re doing something creative.

Eventually, it got harder to do that as music became digitized. But I saw an opportunity with restaurants: in the mid 2000s, chefs were becoming rock stars. They would put on a live show every night—creating songs in the forms of recipes, and albums in the form of menus. I found that fascinating. I had the opportunity to take my background of creative and operational work and apply that to working with a chef here in Boston named Barbara Lynch. She was just beginning to double in size and expand through a major expansion into a new part of Boston, so I signed on to help lead that effort. I dove in feet first.

After working with Barbara for eight years, I had the opportunity to launch a new organization with two partners that I’d worked with there. We opened our first place, Bar Mezzana, six years ago, and just kept going with our latest being Black Lamb.

Q: What interests you about working in a creative field, like restaurants or music?

For me, it’s never been about the overall cash flow. As long as we’re paying the bills, I really want to be doing something that I find creative and unique, and that’s localized as opposed to some big corporation and a cube farm.

My goal has been to do something that I find interesting with people I really admire and enjoy being around. You don’t want to just do it for the dollar. You’ve got to feel good about it, or else the work itself will be uninspired.

Q: What do most people get wrong about opening a restaurant?

It’s easy to romanticize this industry. You think you’ll be like Sam Malone in Cheers, this gracious host hanging out and hosting a dinner party every night. But running a restaurant is a really difficult low-margin business that is impacted by every variable you can imagine—bad plumbing, snowstorms, pandemics—just take your pick. It’s a really, really difficult business.

Q: What’s the first thing people should do when thinking about when they open a restaurant?

It’s very easy to get caught up thinking about what kind of silverware you’re going to have or what kind of art you’ll have on the walls, when in fact you’ve got to go way upstream to the one question that matters: Is this going to be a viable business?

How I’ve always done it is to start with a menu. You have a menu you’re excited about: what can you charge for it? What is the cost of goods (COGS) to create it?

It’s no different from a widget company—that widget has a certain cost associated with it, and you can sell it for a certain amount. It’s not that we never get excited about the rest of the concept—what it will look like, all the details—but if your idea is not going to work as a business, then you’re getting carried away.

Q: What’s an example of how a new restaurant owner might get carried away?

I see a lot of young chefs do this. They might see a corner spot somewhere in the city and start to fall in love with the space. Then they do a menu they get excited about. But the reality is, if you really looked inside that space, it could only sustain fourteen seats. Then you realize, if it’s only going to have fourteen seats and this is the menu I want to do, I’m going to have to charge $200 for a hamburger.

The standard is you don’t want your occupancy costs to be greater than 10% of your revenue.

This is where that creative tension shows up: finding the balance between your restaurant concept and the business metrics. You have to start with a menu you’re excited about, figure out how much you can sell it for, and then calculate how big of a space you need—only then can you start to get excited about renting spaces. Granted, sometimes opportunities come up and the space presents itself before you even have an idea. That’s happened to us, but you’ve still got to go back into your business plan to make sure it makes sense.

Q: Going back to prioritization, what else should you focus on when opening a restaurant?

The biggest challenge I have seen—and maybe it’s unique to Boston in some ways—is there is no sequence to opening a restaurant. Everything is kind of dependent on everything else, and they all have to happen at the same time.

It’s really insane. You don’t want to sign a lease unless you have a liquor license, but in Boston, you can’t secure a liquor license unless you have a signed lease. You don’t want to commit to buying a liquor license unless you have financing for that, since a liquor license can cost up to $400,000. But now you’re raising money for a restaurant that’s not open yet to buy a liquor license that you don’t have a lease for yet. This is unfortunately where the monkey and the pedestal idea falls apart because there is no one thing that you can do first. You basically have to push everything forward an inch at a time. It’s this catch-22, and that’s why it’s so challenging.

Q: How do you deal with everything having to happen at the same time for an NRO?

You can cover yourself by having contingencies with your contracts. For example, with a liquor license, you could negotiate an agreement that’s contingent upon you finalizing a lease and vice versa. The restaurant leases we do have cadences that say they’re contingent upon us being approved by the licensing board in the state of Massachusetts to actually get a liquor license, so that if we don’t get that, we can back out of the lease. Then the landlord can protect themselves by putting in a certain timeline that we have to comply with.

Q: How does Hone fit into the process of opening and running a successful restaurant?

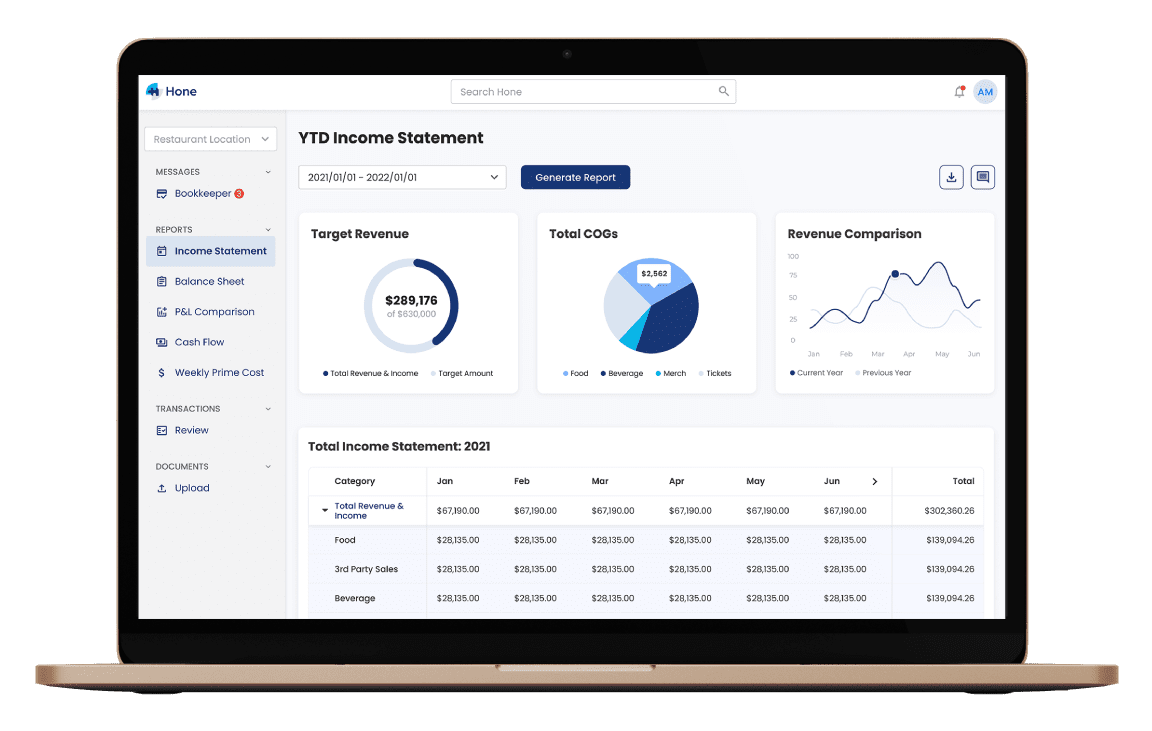

At the end of the day, you’re only as good as your business model—and that means that you’ve got to worry about your sales, your cost of goods, and your labor. We’d be foolish not to take advantage of technology to help us with that.

In general, we try to work more on our business than in it. With restaurants, it’s so easy to get caught up in that vortex. Whether it’s a labor shortage or the pandemic, you’re constantly getting pulled into working in the business, instead of on it. For us, Hone offers an opportunity to spend less time on the grunt work assembling data because it automatically assembles it through the systems that we use in the restaurant. Then we can actually look at those numbers and figure out what changes we need to make.

Q: What other advice do you have for new restaurant openings?

Find good partners and people to work with. In everything we do—contracts, leases, and more—we have a trusted legal advisor.

For example, when it came time to get a liquor license for past restaurant openings, we had a really good licensing attorney. When it came time to do a lease, we had a really good real estate attorney. When it came time to raise the funds and form the LLC, we had a really good corporate lawyer. When it came time to work on the construction budget, we had a really good trusted contractor. In each of these cases, it wasn’t all falling on us. We used our network and we had established relationships to help us in each of those areas, which is what helped us move it all forward.

Overall, this is a really difficult business. We never believed our future success was in any way guaranteed, and it’s still not guaranteed. Running a restaurant is not for the faint-hearted, but if you’re really into it, it can be an extremely rewarding business. We’re proud of what we’ve accomplished so far, but we still have a long way to go. We just try to keep fighting the good fight every day.